What Gay Pride Means To Me

I grew up in a small liberal city in Upstate New York amongst a community of mostly accepting and welcoming people. My coming-out process was probably dissimilar to the struggle and shame many individuals experience during this pivotal period. I was blessed to have supportive parents, a forward-thinking extended family, and a circle of friends who were both queer and straight. Although early into my development as an “out” gay male I stood witness to discrimination and shame experienced by former partners and friends of mine, this was not representative of my own maturation.

I moved to California when I was 19 – more specifically, to the San Francisco bay area. It was there that I developed a more colorful understanding of true diversity of ideas, people, sexualities, and ways of interaction. I became friends with queer people of color, individuals who identify as trans, and learned verbiage that dismisses sexual and gender binaries and conformity. I volunteered my time event planning for a LGBTQ “youth space” in the south bay, from which many members represented the impoverished and homeless queer population in that area.

It was during this time that I felt my understanding of what it means to be a queer person in America was exponentially expanded – with the many backgrounds of sexuality, race, socioeconomic status, and culture all coming together to form a colorful picture of experiences.

My First Gay Pride

It did not even occur to me that my hometown in Upstate New York has held a gay pride parade annually for almost 30 years during my first year in California. I recall being confused when invited by friends of mine to join them for the San Francisco pride parade in 2012. What I found even more confusing was that I had been invited by straight people. For them, gay pride is a tradition – their parents had taken them since they were children, instilling a reason to celebrate diversity, party, and enjoy the display of colors.

As the street festival proceedings took place in the Castro district that Friday night, I remember thinking: this is awesome. Gorgeous men everywhere, drinking on the streets, DJ’s and dancing on every block…and so followed the rest of the weekend, with an absolutely beautiful day in Dolores Park on Saturday, and a terrifying, yet electric parade display down Market Street on Sunday. As the festivities began to wind down Sunday night and I hopped on Caltrain to head back to my place in the valley, I felt like I was coming down from a high that left me fiending for more. Never before had I been exposed to so much energy in one place before – so many beautiful shirtless men, non-stop partying, a celebration of life and being together.

How Was I To Know Any Better?

For the next several years, I didn’t think twice about associating the meaning of Gay Pride with one thing – party. How naive I was, even as the President of the Queer-Straight Alliance at my college, to not know, or even bother to educate myself on why Pride proceedings take place around the world, how they came to be, and why they are so important.

And so continued my next few years of dionysian regard to the festivities and fun of gay pride. I moved down to Los Angeles to complete my undergraduate degree. Pride street festivals turned into circuit events and pool parties, and come springtime all the talk was about the physical preparations and time in the gym necessary to be presentable for pride.

For me, pride lost its meaning in the same way that one becomes bored of going to the same bar every weekend. It lost meaning because, for me, it never really had any to start with.

Los Angeles Gay Pride 2017

Not too long after the 2016 Presidential Election had concluded, LA Pride Parade organizers announced that the 2017 events would be replaced with a protest march. In an interview with Brian Pendleton, nonprofit board member who helps plan the annual event, he stated “We’re getting back to our roots…We will be resisting forces that want to roll back our rights…” Naturally, this shift created widespread upset throughout my friend circle, with Facebook statuses expressing the sentiment “can’t we just have one day to ourselves to celebrate our community?”

It was at this moment that I finally came to learn the true meaning of gay pride. I read about the Stonewall Riots, the first LA Pride Parade in 1970 police threatened to shut down with use of force, and the evolution and importance of this annual event within the context of LGBTQ rights in America. It finally made sense to me – pride began as an expression of resistance, and as a fight for equality and recognition. Its evolution into a celebration is not just a celebration of diversity and difference, but necessary recognition that the fight still isn’t over.

Has The Message Gotten Lost?

I doubt that I am alone in my initial, yet substantial misunderstanding of pride. Furthermore, my innocent misconception of this annual event comes as someone who is fully out – I can only imagine the message contemporary gay pride parades send to straight communities. I have more recently stumbled upon several articles written by queer individuals who call out straight people for attending pride parades, getting recklessly drunk, and treating it like any other party. But how can you blame them?

The increased visibility and amplification of these parades across the country has resulted in a motivation to monetize off fabulous pride parties and create a spectacle that showcases ripped bodies and bright displays, causing a watering-down effect of the message behind pride. While I think these festivals and parties are essential for us to come together and celebrate our diversity, I find it just as important to remind ourselves of the struggles our community has endured thus far, and the struggles which lie ahead.

Is Oppression Necessary To Remind Ourselves?

I certainly hope this is not the case, but at a time in which brands like Absolut who sponsor gay pride parties have more influence than pride participants, I have to wonder.

Andrew J. Pierce, a Doctor of Philosophy whose expertise lies in social ascription, published a paper entitled “Collective Identity, Oppression, and the Right to Self-Ascription” in which he offers the idea that oppressed groups come together non-intentionally. As a result of the lack of freedom or equality, these groups are effectively denied any sort of recognition or “self-clarification,” as he calls it. In this way, conflict is an inherent component of the nature of group identity among oppressed or marginalized groups.

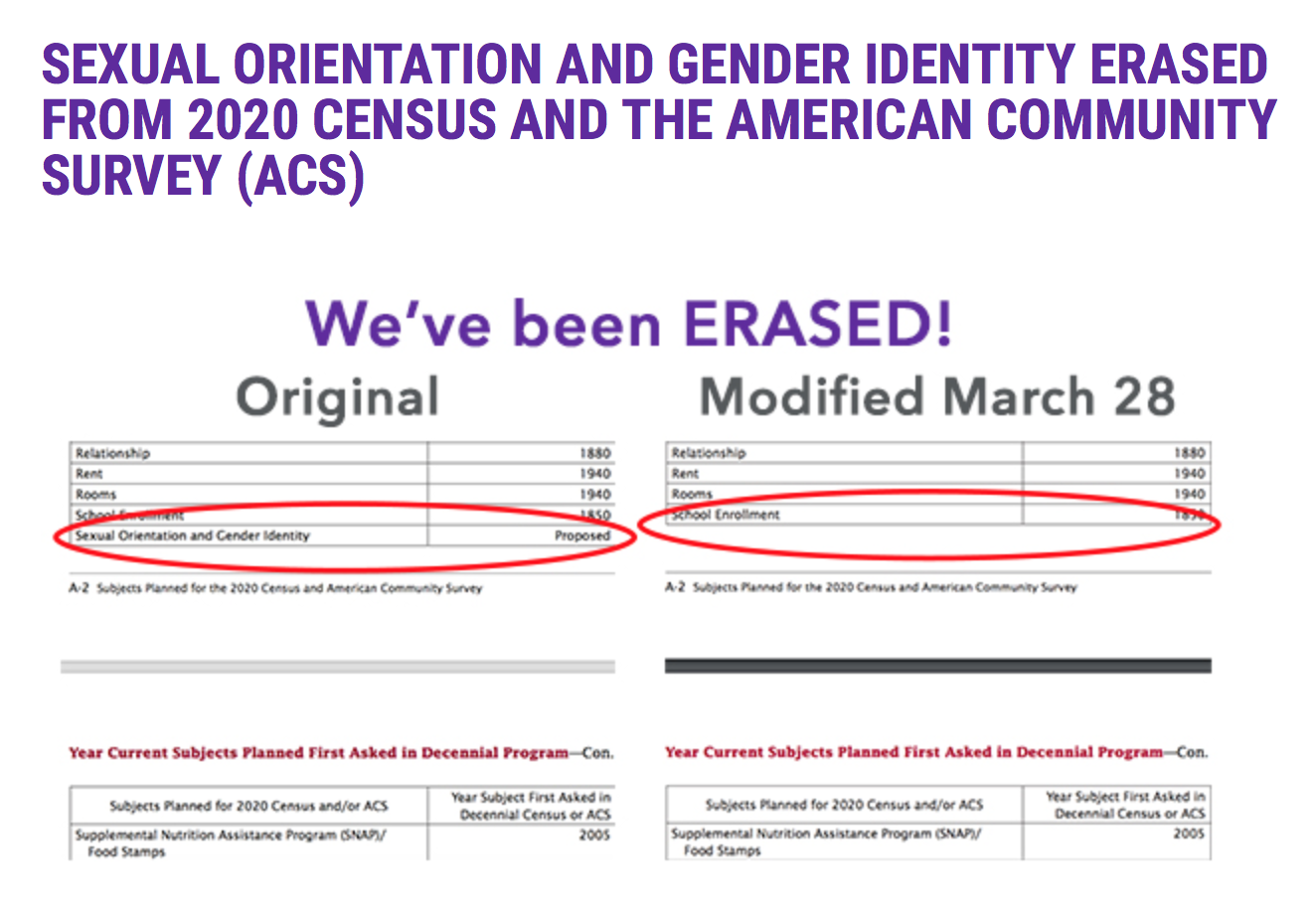

The blatant social regression brought on by our current political environment directly reflects this lack of recognition cited by Pierce, bringing to surface the necessity to be reminded of the meaning of pride. The planned 2020 Census and American Community Survey has been modified to omit LGBTQ people at large, the Trump administration rolled back Obama-era legal protections allowing transgender students in public schools to use bathroom facilities corresponding to their gender identity, with many more regional and federal rollbacks both in process and ahead.

Where Does That Leave Us?

It appears that LGBT individuals in leadership positions are beginning to recognize the flawed nature of our gay pride parades. We are in a time where being reminded of the true meaning of pride is a necessity, especially for our emerging LGBTQ youth who are just now being exposed to gay rights in our current political climate.

To me, pride is still a celebration. I think it should continue to be a celebration of diversity and our differences, but only if we do not lose sight of the recognition that pride is also a resistance. I think that pride campaign verbiage, entertainer choices, and party themes should be colorful and fun, while still reflecting and continuously educating participants on the issues at hand, and how we can lend ourselves to those causes.

Pride is a celebration, and should be a celebration. But pride is also a necessary display of public dissent. Bringing these ideologies together? This is a goal I hope pride organizers around the country will aim to tackle this year, and in the years to come.