Of Course I Have Social Anxiety – I’m Gay

It was my senior year of high school when I got the question: “Are you gay?”

Heather, my ex-girlfriend and then best friend, was standing in the doorway of the band hall when she asked me. Our friend Davis looked on. He was quizzical, she was angry. They looked like they had just been talking about me. I don’t know if I overheard them or made an assumption. Either way, it scared me. Not the question itself. Okay, the question was 10% of the fear. But I had been asked the question before. I had grown accustomed to lying, denying, and faking. I said “no,” just like I had before, with enough believability that they would never ask me again. What scared me, the other 90% of my fear, was the question I now asked myself: were they talking about me? If they were talking about me, if they were compelled to discuss the possibility that I might be gay, that meant they saw through the lying, denying, and faking. Maybe they saw through me. And there was nothing more terrifying than the idea of someone knowing the real me.

Heather had given me the chance to come out. In retrospect, I had a lot of chances to come out, and I was too weak to take them. I don’t have an excuse like other gay kids. I didn’t go to a conservative church. I was never forced to play football against my will, even though I grew up in Texas. My parents never hit me or drank or did anything other than love me. So why didn’t I come out? I could chalk it up to homophobic micro-aggressions. Or witnessing the ridicule that befell the only out student in the school. Or that I’m annoyingly sensitive to other people’s opinions of me. Regardless, I know I wasn’t ready because I didn’t come out. It’s self-evident; if I had been ready, I would have come out, and I didn’t, so I wasn’t. I still needed that protection. I needed the lying, denying, and faking to survive. As I looked at Heather in the doorway of the band hall, I learned that if I get close to someone, they could uncover the part of me I was not ready to accept. They might get to know me, which would mean they would hate me. And it wouldn’t be a surprise because I know me, and I hate me, too.

The Next Question: Is My Entire Life A Lie?

Heather and I were on again, off again throughout high school—an adolescent version of Ross and Rachel. When I finally came out to her a year later, she asked, “Was it all a lie?” At the time, I didn’t have an answer. Technically, yes. I had been lying. I had been lying and denying and faking. I could see both of us reflecting back on our entire relationship with a new light, or maybe newfound darkness. Every memory was now jaded by the undercurrent of my lie. The memory of playing Spades with her. Being drum majors together. Hanging out at the mall or Starbuck or the parking lot of a McDonald’s because those were the only options we had. We were best friends. Or were we? How can my best friend not know the biggest thing about me? And how could I, her best friend, not have told her until now?

I have since learned that our friendship wasn’t a lie. I shared parts of myself with her that were true. I’m pretty good at card games. I loved being a drum major because I love to teach people. Spending one-on-one time with my friends is profoundly important to me, even if that means sitting in the parking lot of a McDonald’s. I saw all of my high school friends dating girls, and I thought this is how it felt to like a girl. To like a girl. I did what I thought I was supposed to do because everyone around me told me it’s what a normal, acceptable person would do. I mistook my friendship with Heather as a romantic interest. Yes, technically I had been lying to her, but I didn’t know it because I was also lying to myself. I had been showing everyone a stencil of myself, a stencil I skewed just enough to form the outline of the person I was supposed to be. Sure, it wasn’t the absolute honest me, but there was still a trace of me there.

The Massive Task of Unpicking the Parts

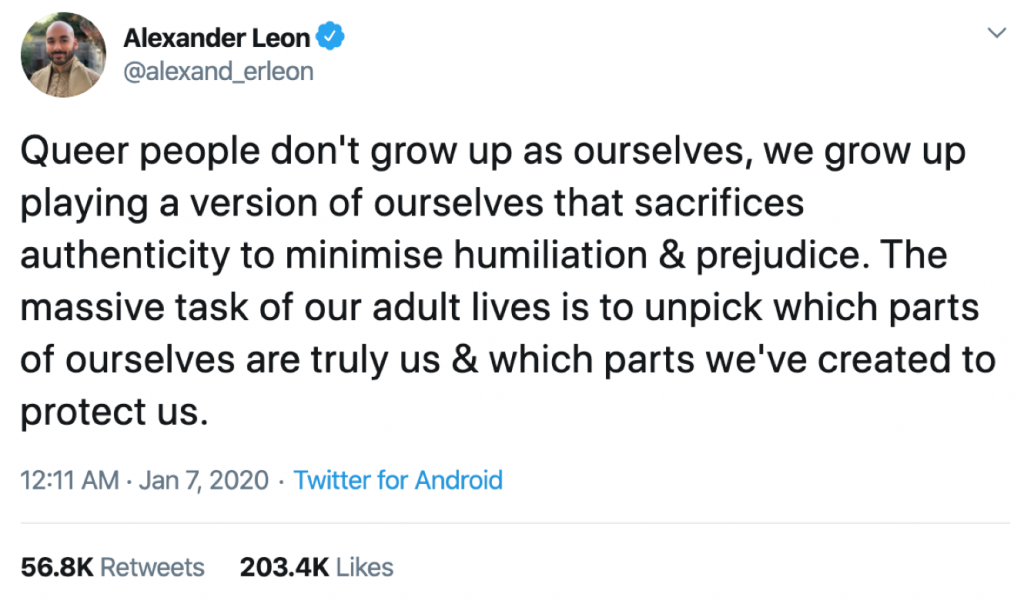

Earlier this year, Alexander Leon (LGBT writer and activist) tweeted a far more succinct explanation of growing up closeted:

The tweet went viral with over 200,000 likes. Alexander struck a universal truth that I could relate to, that most of us could relate to. He summarized the feeling I’ve had my entire life in two sentences. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve forgiven myself for staying in the closet for twenty years. I wasn’t ready, and that’s okay. I’ve forgiven myself for the lying, denying, and faking. Coming out of the closet was an important step towards self-acceptance. Now, I was tasked with trying to understand which parts me were real and which were fake. I had to start at the beginning, asking myself the very basic of questions. What do I want? What do I like? Do I actually enjoy watching football? Do I think beer tastes good? Is this how I walk? Is this my real voice? Yes, I had to question my own voice. The words, the pitch, the timbre, are they all subconsciously constructed to appease those around me? Are there pieces of myself in there? I was a child again, learning how to talk. It wasn’t going to be easy. Luckily, I quickly learned that I don’t actually like football or beer, so that was one more step towards self-acceptance.

Managing Social Expectations and Authenticity

In college, the expectations of a gay man were clear. I was to be the gay best friend; women I didn’t know that well were suddenly talking to me about boys and clothes and going out. I was expected to provide comic relief; I joked about how much I hated sports and beer, even though it turns out I was just indifferent. I should be fashionable, outgoing, bubbly. A social butterfly. I doubt anyone told me directly that those were the expectations, but my assumptions were not unfounded. In Will & Grace, gay men were there for comedy. In Queer As Folk, gay men took drugs and danced all night. In Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, gay men expect that a haircut, a new outfit, and three days’ time could make everything better. Don’t get me wrong; all of those shows were important to advancing gay rights in their own way. But I saw those as the examples of who I was supposed to be. Examples that were reinforced by the gay friends I made who were funny and outgoing and happy. So I tried to be like them. Sure, I had come out, but I was still tracing a skewed stencil of the person I was supposed to be, a different person than before. At least it was a better drawing, a more honest lie.

How Social Anxiety Affects Gay People

One of the characteristics of social anxiety is a persistent fear of social situations in which the person is exposed to possible scrutiny by others.[1] In other words, my default state was social anxiety. I didn’t realize how deeply ingrained in me it was. I couldn’t. It was a part of me. Heather and Davis weren’t the only people that suspected me, and they wouldn’t be the last. I had to be even better at burying my real self. I had to be even more cognizant of how I acted around other people. I studied every move they made so I could do better at picking up the clues. I had to make sure they liked me, but not enough to get too close. I mirrored their mannerisms to fit in without standing out. I liked the things they liked and hated the things they hated. My fear of being found out, of being outed, meant that I had to work a hundred times harder than everyone else just to be in the presence of other people. A simple “hi” from a friend could be a warning sign. Why didn’t I get a full “hello”? They said “hello” yesterday. What did I do between then and now to make them angry at me? Did I deserve the “hi”? What do I need to do to get back in their good graces without seeming too desperate? Analyzing every single word and movement is exhausting. Being around people is exhausting. And no matter how hard I work, there’s always the risk that someone will spring the question on me, “Are you gay?” which is just their way of asking, “Are you the terrible person I think you are?” I had to be on guard all the time, and it was second nature to me. Of course I’m afraid of social situations. Of course I have social anxiety. I’m gay.

For better or worse, this level of paranoia was a helpful defense mechanism for a closeted kid. I learned it for a reason: to avoid suspicion and keep myself safe. But because I didn’t realize I was doing it or why, I brought it with me after coming out, even after I stopped needing a defense mechanism. After coming out, I picked up some new tricks. Being gay meant that I already had one strike against me, so I had to work even harder to fit in. I learned how to use it to serve my purpose. Straight people laugh when I say I don’t understand cars. Straight people are fascinated by Grindr, so I talk about it. Straight people expect me to have an opinion on fashion, so I figured out what styles were popular to better fake interest. Straight people get to ask me if this person is gay, or that person, or that person. And even though I can’t actually tell based on appearance, I would make up a definitive answer and call it my gaydar. Straight people like the gaydar. Even though I had come out, I was still the scared closeted kid that was afraid of being found out. Even though I had started to unpack the surface level things about me, like beer and football and my voice and my walk, I had not yet dug deeper into my learned behaviors, my issues with perfectionism, my fear of criticism and rejection. I hadn’t yet figured out who I really was.

Recognizing Our Own Defense Mechanisms

Not every gay person has social anxiety. Each of us adapted to our circumstances in our own way. We all built our own defense mechanisms to survive, and it’s time to move past them. It could be social anxiety, depression, anger, drug abuse, or something else entirely, but odds are, there’s something there that is worth understanding. If you think you don’t have any residual, maladaptive defense mechanisms, you’re either the most well-adapted homosexual on the planet or you’re lying to yourself. It’s okay. Lying is second nature when you’re closeted. So I suggest taking a look regardless. To understand your defense mechanisms, you have to understand yourself. For me, that meant going to therapy and, in turn, learning that needing help isn’t a flaw. As a cis man, I was taught from a young age that needing help makes you weak, that showing emotion is “gay.” This is just one more way society makes us feel shame for who we are. You are not weak by admitting you need help. You are human. While I believe every human should be in therapy, there are other options, such as talking to friends and family, medication, or meditation. What matters is finding a way to learn about yourself, which leads to understanding yourself, which leads to growth. Instead of being a random sum of your traumas, you get to decide which parts of yourself you want to keep, and which no longer serve you. You get to Markie Kondo your soul.

The Research into Social Anxiety and LGBT People

Unfortunately, research studies don’t provide hard data on how social anxiety impacts LGBT people. For lesbian and gay people, the data focuses primarily on depression and anxiety, of which social anxiety is just a subset.[2] There are a plethora of studies that show gays and lesbians are at an increased risk for mental health issues, including depression, anxiety disorders, suicidal ideation, and others. However, I could find little research on the specific topic of social anxiety, as a distinct disorder from overall anxiety. A case study based on one person—just one—acknowledges that “recent evidence suggests that gay men report more symptoms of social anxiety when compared to heterosexual men.” Why aren’t there more studies on LGBT people’s experience with social anxiety? Does anyone care? Is what I’m feeling real? My hypothesis is that depression is studied more often for a reason.

Why Does Depression Saturate the Narrative?

For most of my life, depression has been my main mental health issue. When I’m depressed, I don’t check my mail. I can’t. I don’t have the energy. I just don’t care. And that’s how depression makes me feel about life: I just don’t care. Depression has a way of clouding everything else, including other mental health issues. I didn’t even realize I had social anxiety until last year. Or at least, that’s when I was first able to put a label on what I was experiencing. Recently, my therapist told me that my depressive symptoms had, thanks to medication and talk therapy, reduced enough that my primary diagnosis was no longer depression. It was social anxiety. Social anxiety was the most important mental health issue I could address. This was mind-blowing. It was exciting. I can work through my issues. I have a chance for happiness. Me! Then again, it was terrifying. I couldn’t deal with having one more thing wrong with me. I couldn’t do it. My therapist told me that it’s going to be there, whether I choose to address it or not. The mail is in my mailbox, whether I check it or not.

There are plenty of examples of how my life is overrun by social anxiety. When I meet someone, the stress overwhelms me so much that I disconnect for a few seconds and don’t remember the first few sentences of our conversation. I don’t ask Lyft drivers to turn on the air conditioning in their car, even when I’m hot because that might annoy them. During job interviews, I sweat through, no exaggeration, one-third of my shirt by the end of them. But the best way I can describe social anxiety is standing in the doorway of the high school band hall. The feeling of their eyes piercing me, trying to dig up the worst of me. Judging me. The realization that I’m not good enough at faking it. I’m not good enough. That’s what I learned. So now, I always think everyone is staring at me. Everyone is judging me. They can see that I am not the gay man I’m supposed to be. I am not Will or Jack or Brian Kinney or Emmett or any of the Fab Five. Every social interaction is an opportunity for my flaws and imperfections to spill out. They can’t. They aren’t allowed to. If they did, my life is at risk. Or, at least, it was. Social anxiety was the coping mechanism I needed to survive growing up closeted. But after I came out, I kept it. I’ve forgiven myself for not coming out sooner, but I haven’t forgiven myself for holding on to my coping mechanism long after I stopped needing it.

Learning How to Manage Social Anxiety

I’m working on not hating myself. On understanding who am I and what I want. On being myself, even at the risk of being rejected. I bought the workbook my therapist suggested. I ask the Lyft driver to turn on the air, even though it makes me unreasonably uncomfortable. I buy black shirts so that when I sweat, it’s less noticeable, and I’ll have one less thing to be anxious about. I give myself compliments in my head. It feels forced. I guess it is forced because I don’t totally believe them yet, but I do it anyway. I share myself—all of myself—as honestly as I can. I’ve discovered that, not only do my best friends accept me, they help me manage, especially when they know I’m struggling. I’m willing to be honest with them. I’m no longer lying or denying or faking. I’m being honest with them. If someone asked me today whether I was gay, I’d say yes without hesitation. I’m no longer tracing a stencil of who I’m supposed to be. I’m throwing away the stencil and showing everyone the real drawing underneath. Letting them see the real me. And against all odds and expectations, I think might I like the real me.

[1]According to the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Source: https://socialanxietyinstitute.org/dsm-definition-social-anxiety-disorder.

[2] For bisexual and transgender people, studies are minimal or non-existent, an unfortunate example of bi and trans erasure.

Kyle is the co-host of Gayish, three-time nominee for Best LGBTQ Podcast. Kyle’s writing has been published in literary journals such as The James Franco Review, Arkana, and Cat on a Leash Review. More info available at kylegetz.com.