Forgiving Your Parents – A Coming Out Story

She remained quiet behind his unwavering belief that who I was and what I stood for was a sin. As I sat there and watched her submit to him with her head down, I knew I was in the midst of a losing battle but that I still had to be courageous and fight for what I believed in. What I believed was that I am worthy, I am enough, and I deserve to be loved just as I am. Like most serious conversations in my family, my father did all the talking, except that for this one, in particular, the things my mother didn’t say were what hurt the most. The looks of guilt, regret, sorrow, and compassion are forever frozen in my memory as my Mother mustered up the courage to lift her head up and face me. Although she appeared sorry that it had to be this way, the words “I’m sorry” to this day have never been saying.

I initially tried to enter the conversation without any expectations, but I suppose that in the back of my mind I had hoped to hear that my parents still loved me, and I would be reassured that no matter what struggles we face in life – we are family, I will always be their son, and we are here to support each other.

When things went the opposite direction, and I was met with disapproval and opposing viewpoints, I became exposed to the lengths a woman, and a mother, my Mother would go through to stand beside (or should I say behind) her husband, even if it meant being dismissive of the vulnerabilities of her child. I anticipated my Dad having the reaction that he did, but I was shocked that my Mother did not so much as attempt to stand up for me when I thought we were close. Devotion to one’s spouse is truly an admirable trait, but not whenever you choose to ignore other principles that are fundamental to a child’s self-esteem, self-worth, sense of trust, and security. In return, the repercussions of this had a lasting effect that I would find myself struggling with throughout a variety of relationships for the next 20 years.

I understand that it was a different time back then, but I wondered why my mother could not speak for herself. Why did she always have to check with my Father first, before making up her mind? Did she have an opinion on the matter?

Why was the fact that I was gay so hard for her to talk about, and what was keeping her from seeing me for who I was, instead of judging me for who I loved?

Being the quiet observer type, I’ve always been sensitive to subtle nonverbal cues, like body posture, facial expressions, and various types of eye contact. What I picked up from my Mother while sitting at the kitchen table was that she felt bad that this was happening. In her heart, she knew that placing the church’s anti-gay beliefs before the love of their child wasn’t right. The type of rejection I experienced from my parents didn’t look like getting kicked out of the house. It was a quiet rejection, an honest look of disapproval and disappointment deep in their eyes. My attempt in reasoning with my Father by saying that one day instead of having a daughter-in-law, he’d have a son-in-law was ignored while he continued on about what the church teaches.

When he was finished reminding me why being gay was wrong in the eyes of God, he made sure to tell me not to tell Blake, my little brother, who at the time was 14 years old. I was already struggling with admitting I was gay to other people, and I wasn’t the least bit ready to tell my little brother.

It sounds a little silly now, but at the time, I was worried how me being gay might influence him as an adolescent. I’m not exactly sure how it might have affected him negatively, but perhaps the fear was that what if he thought he might be gay too since I was gay- proof that I was truly convinced that being gay was wrong, because if it was right, I certainly wouldn’t be afraid to share the good news. On that note, let’s say that the behavior of older siblings does influence younger siblings, which does happen from time to time. In this case, if the older sibling turns out to be gay, it doesn’t by any means conclude that the younger sibling will be gay too. At most, the younger sibling might question themself or be more open to exploring their own sexuality to find out if he or she is gay or not, but still, being gay isn’t a monkey see monkey do type of situation.

But that was it; there was no use saying anything else because even if my parents heard me, their minds were made up. Being gay was something my Father could not support, and so then neither could my Mother. I tried as best as I could to take a stand against what the bible teaches, thinking that maybe since they saw their child struggling, it might spark some compassion in finding an exception to the Catholic rule. I was not committing a crime, except maybe in the eyes of God and the church, yet they still could not bear the thought of me being the person that I was – a person who simply wanted to love and be loved without having to hide. After multiple failed attempts, I was hurt, angry, and overwhelmed. I buried those feelings with other characteristics about myself that I learned were not welcome around my parents – characteristics like being vulnerable, expressive, and open. Instead of being who I wanted to be, I suppressed myself once again as I momentarily yielded to who they wanted me to be while masking the pain of not having their support with dignity and grace.

Many of us can probably recall our parents saying to us at one time or another that all they want is for us to be happy. Generally speaking, this is a common dynamic between the parent-child relationship – parents wanting their kids to be happy, and kids wanting to make their parents happy.

It’s an innate and conditioned relationship because our parents gave us life, our Mothers birthed us, and so we not only love our parents but want to thank them by doing right by them. From the moment we are born, our parents give us positive reinforcement for good behavior or punish us for bad behavior. We are conditioned with a long history of sharing our wins and losses together, and in doing so, begin to validate ourselves through their responses. Whether it’s from when we were babies finishing our entire plate of food, as kids eating all of our vegetables, getting good grades in school, or performing well in sports, the need for approval and validation by our parents is something we attach ourselves to and in a sense become defined by. After all the effort I had given to make both of my parents happy, I felt my Mother’s inability to find a compromise between her husband’s opinion while supporting her child was the highest form of rejection, and I felt betrayed. She and I were close growing up, and I considered myself a proud mama’s boy, but on this night, the love and bond I thought we shared was gone. Clearly, the bond, nor I, was enough to stand the test of traditional family values.

We ended the conversation without a resolution and agreed to disagree. This is why the night I came out to my parents became one of my biggest cornerstones in life, a memory that I hold on to that defines a major component of my identity. Still, to this day, our conversation has never been resolved, which leaves the topic hanging in limbo. To my parents, me being gay is neither dead nor alive, and it reminds me of lyrics to a song I heard by The Lumineers that proclaim, “the opposite of love is indifference.” My parents are indifferent about my homosexuality, and even though I’m not completely ok with their indifference, I’d rather spend the time we have together loving them instead of hating them.

When I left the house, I cried to myself in the car for almost an hour and a half as I drove back to Austin. My parents’ house was in San Antonio, and I drove down two weeks before I graduated from college just to have this conversation with them. My intention was to enter the next chapter of life with a little less baggage, except that in the process of letting go of one burden, I picked up more. On the way home, I kept saying to myself that I was ok and that nothing really changed because even though my secret was out, I would continue to move forward just as I’ve always done without their support.

Although I put up a good fight, my confidence and self-worth took a huge hit. I pretended to be strong for many years. “Strong” to me meant denial, suppression, and dishonesty about my feelings. Years later, after a long stint of abusing drugs and alcohol, I learned how to remove my ego, face real, raw emotion, and discover what was at the bottom of almost everything I was running from. On the night I came out to my parents, I translated and internalized everything they said and didn’t say as, “You are not enough” and, “You are not worthy of the kind of love that will accept all of you.” I can’t attribute all of my insecurities to that moment in time, but my parents not accepting me felt like a major source of where a lot of my issues of self-acceptance and trust in relationships came from.

My best friend said something to me once after we got into a huge fight that I don’t think I’ll ever forget. He called me a “fierce independent” because of how I push people, including him, away every time they start getting too close. He was always trying to dig into my behavior and psycho-analyze every move I made, but even when he was wrong, I admired him for caring and courageous enough to get to the bottom of some of my passive-aggressiveness.

It’s extremely difficult to relive all of this again, but it’s the truth of how I felt at the time. As I look back 20 years later and compare how the relationship with my parents has changed from then to now, I acknowledge that I may have set myself up for unrealistic expectations. Once I was able to separate the need to feel validated by other people, specifically my parents, in order to be happy, I entered the possibility of forgiving them. In the big scheme of things, although they raised me from birth, my parents are just people. They come from a different time and place, and I had to ask myself if it’s fair of me to force my lifestyle on them. True, I wasn’t overtly forcing my lifestyle on them, but I was adamant about them being ok with something they weren’t comfortable with. It’s not fair for anyone to decide how other people ought to feel about anything. Having an opinion is great, but we can’t get hurt every time something doesn’t go our way, or someone disagrees with us. Perhaps what I was seeking at the time I came out to my parents besides their support, was for someone to fight for me and stand in my corner. Whenever they did the opposite, it not only drew a dividing line between us, it taught me a hard lesson. The lesson was that I was the only one who could fight for the life I wanted to live. I learned not to depend on others to do for me what I had to do for myself and so, and if I wanted to follow my heart, and live my truth, then it was up to me to make it happen. For that, I thank my parents for opening my eyes.

Twenty years later, my sexual orientation is still not a topic of conversation. My parents don’t want to know who I’m dating or if I’ve met someone new. Whether or not it’s because I’m gay, I’ve stopped making it about that and started making it about them. Instead of putting so much thought towards what my parents think about me and my personal life, our topics of conversation revolve around work, the lives of my other siblings, their kids, birthdays, holidays, vacations, what they did that day, or are having for dinner.

When I need to vent or talk about something personal or related to being gay, I have other people in my life for those conversations outside of my family. When I look at things from this perspective, it makes a lot of sense why being vulnerable has been one of my biggest opportunities in life. Just because I wasn’t shown how to be vulnerable, love, and accept myself for being different while growing up, it doesn’t mean it’s too late to start now. The best way for me to practice the vulnerability that I lack is by being honest in the relationships that I have with others today, and by openly sharing my story. If I’m feeling insecure about something, I talk about it, write about it, or post about it. If someone reads, agrees, or leaves a comment, then that’s great because I have just made a connection with someone who understands and most likely has experienced something similar, and we are able to support each other and grow through it together. If I get no response or likes, or if someone laughs or disagrees, then that’s ok too, because I have just practiced a healthy way of letting go by being honest, open, and vulnerable. Sometimes it’s tough putting yourself out there, but it’s all part of learning how to be comfortable in your own skin.

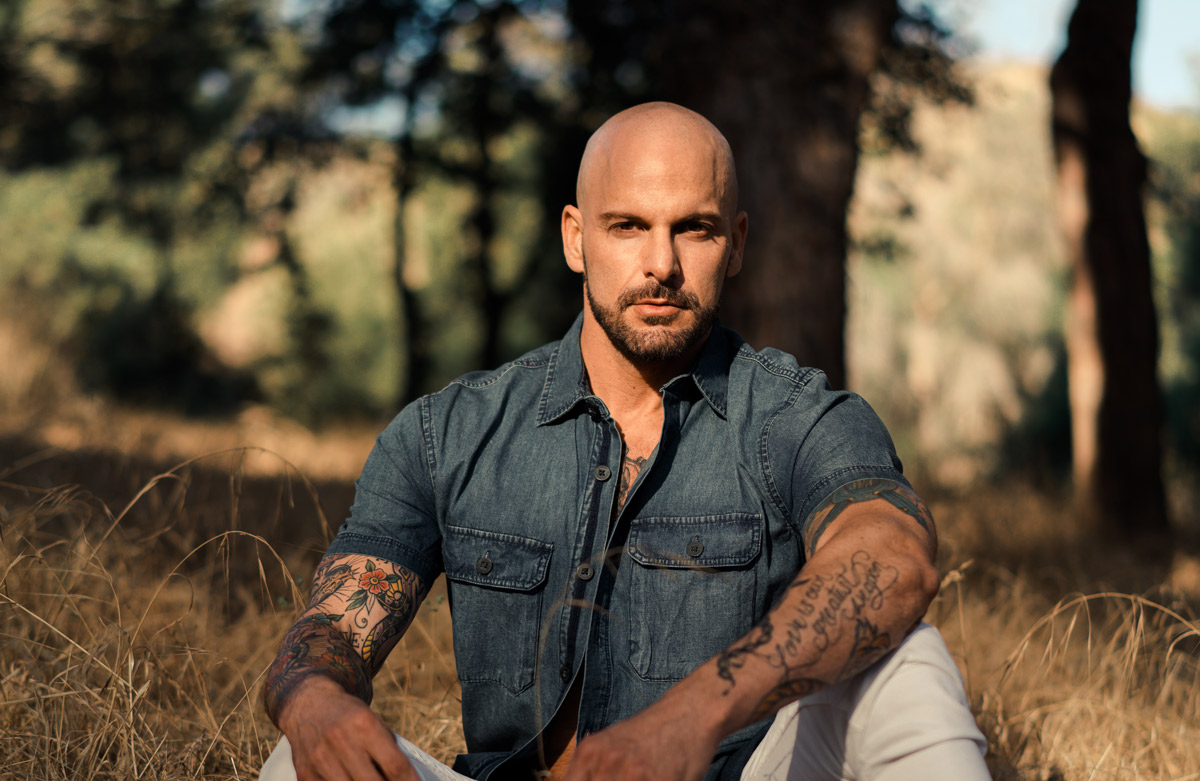

Author’s Bio: Danny currently lives in San Diego, California and has published pieces in DNA magazine. If you’d like to connect further with Danny, you can subscribe to his website, dannyjmarino.com or follow his blog on Instagram @thepursuitofsex Photographer: Lester V. IG:@shotbylester