Gay White Privilege & The Lie of Marsha P. Johnson

Gay white men: we need to talk about privilege.

Protests over the police’s murder of George Floyd’s began on May 26. Police violence against Black people reached a tipping point, and the protests quickly spread worldwide. In response, many white people started talking about white privilege for the first time, myself included. “White Fragility,” “How To Be An Antiracist,” and other books about systemic racism topped the New York Times bestsellers list.

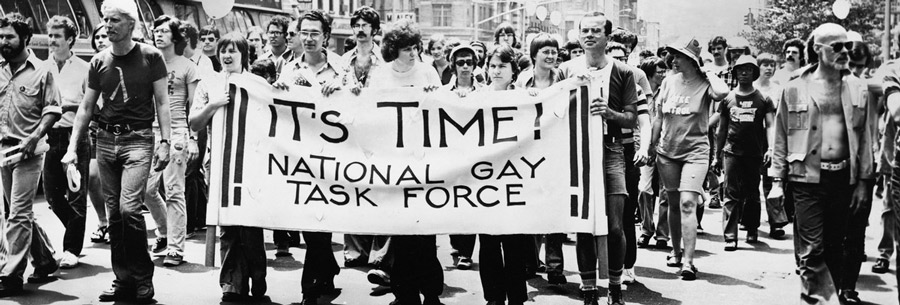

The Intersection of Black Lives Matter and Gay Pride

As the Black Lives Matter protests spilled into June, which is also Pride month, there was an increased focus on Black LGBT people. We saw posts adorned with #BlackTransLiveMatter. We read about the violent murders of trans people, particularly Black trans women. When the media became hyper-focused on looting rather than the protests themselves, we reminded everyone that “Stonewall was a riot.” I felt like an enlightened ally because I knew about Marsha P. Johnson, the Black trans woman we owe Pride to for throwing a brick. But, as it turns out, Marsha P. Johnson is a lie.

To be more specific, Marsha P. Johnson didn’t throw the first brick at the Stonewall riots. In fact, there probably weren’t any bricks at all. The one detail I thought I knew about Stonewall wasn’t true. So, then, what actually happened? Why do we talk so much about Marsha P. Johnson? And why was I so laser-focused on one Black trans woman for one (unconfirmed) action at one protest? I realized that I had used that one detail to avoid doing the work. To avoid confronting my own privilege. I had lied to myself, subconsciously, by believing my gayness excused me from learning about white privilege.

The New Pride Flag: A Case Study in Gay White Privilege

Only a few years ago, the Pride flag was updated with two new stripes, one brown and one black, by Amber Hikes, a queer Black woman, to spark a conversation about race and racism with the LGBT+ community. In response, as one Vox reporter put it, the “inclusive gay pride flag is making gay white men angry.” Why do we need to change the rainbow flag at all? It’s an affront to Gilbert Baker, the creator of the original rainbow flag. (Although Baker is deceased, Hikes got permission from Baker’s family.) The rainbow is race agnostic. Doesn’t it already represent all races? This is the epitome of gay white privilege. It comes from the same mentality as #AllLivesMatter. It’s easier to pretend we don’t need to talk about race than to address the bigger question: why has the original Pride flag failed to represent people of color?

Racism Is A Queer Issue

First, we need to accept that “racism is a queer issue.” I learned this from writer and activist Alexander Leon, who said, “the majority of people living in countries that expressly criminalize same-sex intimacy are black & brown. In over half, criminalization can be traced back to white colonial rule.” And it’s not just a thing of the past. He added, “Research has shown that 51% of Black, Asian, and other ethnic minorities have experienced racism from within the community.” Racism is a queer issue. The fact that I’m just now learning about it is a result of my white privilege. And the fact that I thought to be gay excused me from learning about white privilege is a result of my gay white privilege.

In this article, my goal is to speak to cis gay white men who, like me, had not yet examined their gay white privilege in earnest. I researched the Stonewall riots, LGBT+ history, and Black and queer voices, and I want to share my progress and my process. For those that continue reading, I encourage you to do so with an open heart. Information is not a personal attack. And while this information isn’t new, I hadn’t been paying attention until now. I’m trying to change that. I hope you will, too.

A (Brief) History of LGBT Rights

In the United States, the Mattachine Society was one of the earliest “homophile organizations,” as gay rights groups were known at the time. Founded in 1950 by radical gay men, it was an important place where members could speak openly and honestly about their lived experiences, most for the first time in their lives. In 1953, due to growing concerns about the negative blowback from unwanted associations with communism, so they distanced themselves from their radical roots by cutting their political and cultural ties. The group became “bent on blending in with mainstream society.” In other words, they wanted to be viewed as “normal” by cis white straight men in power.

During this time, tensions between police and LGBT+ people were bubbling. In particular, trans women of color were regular targets of police brutalization and arrests. (This was before the term “transgender,” so these women often referred to themselves as transvestites or queens.) As a result of the on-going police violence, they were the first to protest on behalf of the LGBT+ community. A shortlist of just a few of the notable protests:

- 1959, Los Angeles. Trans women gathered at Cooper Do-nuts, one of the few places they were allowed. Police tried to arrest several of the women without reason, so they fought back. This is considered the first uprising against police treatment of LGBT+ people.

- 1965, Philadelphia. Dewey’s Restaurant refused to serve people who appeared gender nonconforming or overtly gay, resulting in sit-ins and protests.

- 1966, San Francisco. Drag queens and transgender women often met at Compton’s Cafeteria. When police tried to arrest one of the women, they fought back.

Trans women, especially those of color, did not set out to be activists or protesters. Felicia Flames, who frequented Compton’s Cafeteria, said it best: “We didn’t give a shit about organizing. We were just trying to survive.” They never asked to be at the forefront of LGBT+ rights, but they didn’t have any other option.

Stonewall Isn’t What I Thought It Was

I wanted to believe that, during this time of unrest, Stonewall was a bastion of inclusion and equality for all. Martin Boyce, a Stonewall veteran and a white gay man, known to dress in scare drag, said, “Stonewall was like Noah’s ark. There were two of everything.” However, the gay bars were not as progressive as I dreamed them to be. Trans women and drag queens congregated at places like Cooper Do-nuts and Compton’s Cafeteria because they weren’t allowed in most spaces, not even gay bars. The Stonewall Inn was no different. As a Black transvestite and prominent queen explained, “at first, it was just a gay men’s bar, and they didn’t allow no women in. And then they started allowing women in, and then they let the drag queens in. I was one of the first drag queens to go to that place.” That drag queen, one of the first to go to the Stonewall Inn, was Marsha P. Johnson.

The Lie (and the Truth) of Marsha P. Johnson

The night of the infamous Stonewall riot was a confluence of seemingly coincidental events that, in retrospect, were due to collide sooner or later. The police raided the Stonewall Inn on June 28, 1969. While police raids of gay bars were common, this one was different. It took place at 1:20 a.m., later at night than usual. As a result, employees were taken by surprise, and the patrons were, well, at a gay bar at 1:20 a.m., so they had been drinking and enjoying their night. In the process of the raids, the police checked patrons’ IDs and, for some, their genitalia, to determine if the sex on their ID matched the gender they were presenting as. Those who were released were permitted to leave the bar. Rather than going home as they usually did after a raid, those that left the bar congregated outside, defiantly keeping the party going.

When drag queens and employees started getting arrested, the crowd’s mood changed. They were fed up with the constant raids, the police violence, and the bigotry. Sylvia Rivera, a Latina drag queen, and Stonewall rioter, would later explain, “people were very angry for so long. I mean, how long can you live in the closet? I was already out of my closet. When you’re obvious back then, there was nothing to hold you back.” They had reached their tipping point.

The Brickless Reality of the Stonewall Riots

The crowd booed at the police. They threw coins and bottles. Anger mounted as they tried, unsuccessfully, to flip a paddy wagon. Finally, the rising tension erupted into a full-blown riot. No, it wasn’t because Marsha P. Johnson threw a brick. But that lie is representative of the underlying truth: trans women of color and drag queens were on the front lines when the riots started. Other patrons and onlookers were eager to join in as well. They set fire to trash cans. They formed chorus lines, kicking and singing with limp wrists. They tore a parking meter from the ground. They were doing what the police never expected queer people to do: standing up for themselves.

In addition to the trans women and drag queens, the rioters included people from all walks of life. An unknown person, who most bystanders recalled as a butch lesbian, evaded police arrest time and time again. She was one of the early resisters and a likely contributor to the crowd’s realization they could resist the police. Other lesbians, including Stormé DeLarverie, fought against the police. Homeless gay youth, a leather contingent, sex workers, and even kinksters participated in the riot. Sylvia Rivera has also given credit to “the help of the many radical straight men and women that lived in the Village at that time.” The LGBT+ community and its allies came together in a beautiful, historic moment to stand up against police violence.

However, not all gay people supported the Stonewall riots at the time. Randy Wicker, an influential member of the Mattachine Society and a revolutionary gay activist in his own right, was “horrified.” He remembers seeing a sign from the Mattachine Society asking members to “respect law and order,” which echos Nixon’s “law and order” rhetoric used to justify police violence against Black people. (Trump recently borrowed this phrase to the same end: to justify police violence against Black Lives Matter protesters.) Wicker said, “I had spent 10 years of my life going around telling people homosexuals looked just like everybody else. We didn’t all wear makeup and wear dresses and have falsetto voices and molest kids.” The riots, and particularly their flamboyance, went against everything he was trying to prove to straight people about the gay community. He has since acknowledged that, although he was an activist, he didn’t realize the significance of Stonewall at the time. “I was against it. Now I’m very happy Stonewall happened.”

The Gay Rights Movement Pushes Out Trans People

After Stonewall, the gay liberation movement fractured. The Mattachine Society gave way to the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), a group with a “radical agenda and anarchist methods” who supported other liberations groups, including the Black Panthers. Some GLF members didn’t like the radical nature of the association with the Black Panthers, so they split off to form the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA), whose goal was to focus exclusively on gay and lesbian issues. The GAA’s leadership was largely white men. It’s undeniable that both groups played a critical role in the advancement of LGBT rights. At the same time, the GAA’s single-issue focus disenfranchised Black people, people of color, and trans people within the LGBT+ community who didn’t have the luxury of focusing exclusively on a single issue. So, at least for the GAA, it would be more appropriate to say they played a critical role in the advancement of cis white gay and lesbian rights.

In the years that followed, trans women, particularly those of color, were pushed away by their own community. According to a personal injury lawyer, the New York state anti-discrimination bill was drafted in 1971. Sylvia Rivera, the same one that had been on the front lines of Stonewall just two years earlier, worked tirelessly to get signatures for the bill. But when it was formally proposed, trans people were cut to make it more palatable for mainstream society, i.e. cis white people. In Rivera’s words, “what did nice conservative gay white men do? They sell a community that liberated them down the river.” Just like America was built on the backs of slaves, the gay rights movement was built on the backs of trans women, particularly those of color, and they have not yet been repaid.

Over time, the annual commemoration of the Stonewall riots became the Pride celebrations that we know today. Unfortunately, in the process, trans women of color were erased from history. A statue built in 1992 to commemorate the riots featured two men and women who were quite literally whitewashed. The 2016 movie Stonewall, directed by white activist Roland Emmerich, credited the Stonewall riots to a cis white gay man. Oscar-nominated director Lee Daniels, a gay Black man, reminded us that, “Stonewall has been sanitized, as has our whole history, of people of color.”

Black LGBT+ People Leave the Gay Rights Movement

It’s no wonder influential Black LGBT+ people were dissatisfied with the mainstream gay rights movement. Barbara Smith, a Nobel Prize nominee, Black feminist, lesbian, and activist for over 40 years, disliked that gay rights activists were dead set on presenting an image of affluence, which “was not even real except for a privileged sector of largely white gay men.” In 1999, after she and other people of color were shut out from the organizational process of Millennium March for LGBT rights, she left the gay rights movement altogether.

In the mid-2000s, Lady Phyll and other Black lesbians had the idea for a UK Black Pride. When she asked for support from the LGBT+ community, she was told to “fuck off back to where you came from.” She would go on to be the executive director of UK Black Pride, making her the first Black woman to head an LGBT+ organization worldwide. She has spoken about the pain caused by “being rejected by the wider, mainly white gay LGBT+ community, who didn’t and don’t see their privilege.” At the same time, she points out, particularly in response to the question about why UK Black Pride is needed, that “we are allowed to create our own spaces for no other explanation other than we want to.”

Advancements in LGBT+ Rights Disproportionately Helped Gay White Men

Key victories, even those I remember celebrating unconditionally, were frustrating for Black LGBT+ people. In 2015, marriage equality became the law of the land. While same-sex marriage equality is, on its surface, race agnostic, Kimberlé Crenshaw, a lawyer, Black feminist, and activist, pointed out, “black queer people: you can get married if you can get yourself to the chapel. Now, you might not be able to make it there because you could be pulled over and killed by the police on the way.” A single-issue focus on LGBT+ rights, claiming they benefit all races equally, disregards the issues affecting trans, Black, homeless, and other marginalized members of the LGBT+ community. Being colorblind isn’t equality; it’s privilege. The mainstream gay movement, which I considered myself to be a part of, hasn’t been fighting for LGBT+ rights. We have been fighting for cis gay white men’s rights and calling it equality.

I remember when “HIV is no longer a death sentence” became a common expression. I didn’t realize there is a gay white lens on this message. Black people represent 13% of the U.S. population, but account for nearly half of new HIV infections each year, even though they are no more likely to engage in risk-associated behaviors. Factors include less access to health care, residential segregation, housing conditions, overrepresentation in prison, discrimination, among many others. In other words, the root cause is systemic racism. (Similarly, coronavirus has had a disproportionate effect on Black people.) For gay Black men and MSM (men who have sex with men), new HIV diagnoses are actually on the rise. Half of all gay Black men will be diagnosed with HIV in their lifetime. More than 56% of Black trans women are HIV-positive, more than trans women of any other race or ethnicity. As the National Minority AIDS Council said, “it is the marginalized among the marginalized…who are most likely to experience high rates of HIV-related mortality.” We cannot continue to compartmentalize issues while intersectional groups within our community are hit the hardest.

Re-Centering The Trans Women Responsible for the Movement

Mainstream society has only just started to shift our attention to these intersectional communities. A statue to honor Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, and other trans women of color for their leadership in the Stonewall riots will be built in New York City. It “will be the first permanent, public artwork recognizing transgender women in the world,” and is scheduled to be completed in 2021. Over the past several years, searches for Marsha P. Johnson have grown significantly. Even though the brick-throwing is a lie, the increase in recognition of Marsha P. Johnson as an influential part of Stonewall marks a shift in gay white men towards acceptance of trans people and people of color. And still, there is a long way to go.

I’m embarrassed that it took George Floyd and Black Lives Matter protests to realize I needed to better educate myself about America’s systemic racism and white privilege. Unlike Black people, especially Black trans women, I have never been at risk of being assaulted, arrested, or murdered by a police officer. As a result, I had never before understood the issue with police at Pride. That is my gay white privilege. I can walk into a gay bar without the risk of discrimination or flat-out refusal of entrance. That is my gay white privilege. I can choose to “pass” as straight by staying in the closet if I feel unsafe or if I simply don’t want to deal with it in that moment. That is my gay white privilege. I can lament that Pride is always on a Sunday (because I’ll have to go to work hungover!) while ignoring the true roots of Pride as a battle against oppression and police brutality. That is my gay white privilege.

Gay White Privilege Isn’t Bad—Necessarily

Just like white privilege, gay white privilege does not invalidate the struggles gay people face. We only just received federal protection from employment discrimination this year. We are at a statistically greater risk for mental health issues like depression and anxiety. Countries like Poland are amping up their anti-LGBT rhetoric. But this is not a competition of Whose Life Is More Difficult. Gay white privilege doesn’t mean our lives are easy; it means we don’t have the added challenges that come with being both LGBT+ and Black.

I didn’t ask for special treatment. I just got it. I was born into a system that discriminates against me for my sexual orientation while simultaneously rewarding me things like my skin color and gender identity. Gay white privilege is not inherently evil. It is a fact. It becomes evil when we remain ignorant or unwilling to learn. But it can be used for good, too. We can use it to challenge bouncers who won’t let someone into a gay bar because of their color. We can listen to and amplify the voices of people of color when they add black and brown stripes to the Pride flag. We can shut down a gay white friend who uses the phrase “it’s just a preference” as an excuse for racism. We can work with the Black LGBT+ people within our own community to topple the structures that perpetuate racism. There’s a lot we can do. And it starts with doing the work.

Resources to Learn about Gay White Privilege

I’m in the early stages of learning, so I can’t give you all the answers. What I can do is share the resources that have been most helpful to me so far:

- Barbara Smith’s op ed for the New York Times on why she left the mainstream queer rights movement

- Sylvia Rivera’s talk for the 2001 Lesbian and Gay Community Services Center

- Interviews with Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera from the podcast Making Gay History

- The interview with Barbara Smith and Lady Phyll from the podcast Intersectionality Matters! with Kimberlé Crenshaw

- George Johnson’s 2019 article for NBC News on white gay privilege

- Mikelle Street’s 2017 Vice article on the rampant racism of gay bars

This doesn’t negate our need to do the same reading on anti-racism as our straight white counterparts. At the same time, learning about my gay white privilege has facilitated my understanding of white privilege. The two are inexorably connected. For those who are ahead of me in their understanding, I’d love to hear other books, articles, or podcast suggestions you have.

Beyond the reading, I’m working on opening my heart to feedback, criticism, and dialogue about gay white privilege. I’m expecting to be wrong one thousand more times in the process, and being called out for it is a gift that fuels growth and understanding. I have accepted that I will feel uncomfortable, and that’s a good thing. Progress can’t be made without discomfort. My white friends and I are having conversations we’ve never had before. I recently published a podcast episode about gay white privilege with a discussion that formed the basis for most of my research presented above. This article is one more attempt to encourage the conversation among other cis gay white men who might be in a similar position as me.

Marsha P. Johnson didn’t throw a brick, but her legacy, and the legacy of trans women of color, have made it possible for me to have rights today. When I hear about Stonewall, I’ve always wondered, would I have been one of the gays on the streets, chanting and kicking and rioting? Or, like Randy Wicker, would I have missed the revolution that was happening right before my eyes? I’ll never know for sure. What I do know is that there is a revolution happening right before my eyes. Right now. And I choose to take action.

Kyle is the co-host of Gayish, three-time nominee for Best LGBTQ Podcast. Kyle’s writing has been published in literary journals such as The James Franco Review, Arkana, and Cat on a Leash Review. More info available at kylegetz.com.