“Stonewall Strong” Powerfully Speaks of Gay Men’s Resilience

John-Manuel Andriote is an established author, journalist, speaker, and one of the longest-term leading reporters on the HIV-AIDS epidemic. In the original piece below, John reflects on several personal experiences that led to his interest in writing about gay men’s resilience. His newest book is called Stonewall Strong, released this past fall.

Chicago. Summer 1985. I’m a 26-year-old graduate student at Northwestern University, working on a master’s degree in journalism. I follow the news closely because I aim to become one of the men and women who report it. I subscribe to five newspapers and multiple magazines. The Internet, and digital, is years away.

All over the news, especially the gay community’s newspapers, are photos and stories of emaciated men. The captions say they are young, though they look old and frail. Most of them have dark purple spots on their skin. They look deathly ill. The captions also say they are gay men suffering from AIDS.

The plague invaded my own life in the spring when I had a letter from my old boyfriend back in Boston, telling me our mutual friend Michael, in New York, had died. He was 25. I had slept with Michael a couple of times, bottomed for him once. Without a condom.

Michael is my first friend to die from AIDS. A week later I have a phone call from Frank, the hot Italian-American podiatry student from the North End of Boston I first hooked up with at Carol’s Speakeasy, where I love to dance on Friday nights. He wasn’t calling this time for a repeat, but to tell me that our friend Jim, back in Boston, has died from AIDS. He was 30. I had slept with him, too.

I’m not only grieving my friends’ deaths, but I’m scared, too—and wondering how I can help, what I can do.

Then I meet a handsome man with blue eyes and strong arms I was admiring from the side of the dance floor at Badlands, DC’s popular gay dance club near Dupont Circle. I’m in Washington for the fall semester to work as a real reporter for a newspaper in Wisconsin as part of my master’s program.

After we dance, we head upstairs where it’s quieter so we can talk. And we keep talking, especially about AIDS. His name is Bill Bailey.

Bill is a “buddy” with Whitman-Walker Clinic, the gay community’s STD clinic that has taken on AIDS as a natural extension of its work. He helps a black gay man with AIDS, who lives with his family in Anacostia, the District’s largely black neighborhood, to get out of the house when he needs to.

In what I soon learn is his direct style, Bill tells me it’s my “duty” as a gay man, and as a journalist, to use my time and talent to document and report our community’s experiences in the AIDS epidemic.

We keep talking even after we kiss for the first time when he drives me home, in the rain, and our kissing and talking fog up the car windows.

That November night in 1985 I met the love of my young life, and found my life’s purpose.

Through Bill I met many of the men and women in DC who were working to address the epidemic. There was Judy Pollatsek, a pint-size powerhouse of a therapist specializing in bereavement. There was Bob Edwards, and Fred Steen, two of Whitman-Walker’s buddy team leaders. They would be among my regular sources when I began reporting on AIDS in 1986. They would also become my friends.

Bill found out he was HIV-positive in the summer of 1986. We were “off” at the time, one of our regular breakups, but he called me late one evening in July to tell me. By then I was working on my first major feature article on AIDS, a cover story for Washington City Paper called “The Survivors.” It was one of the first articles anywhere to examine the unique issues gay men faced when their partners died from AIDS.

It was hard to ignore AIDS in those days. There was even a tickerboard on the wall of the Riggs Bank that towered above the Dupont Circle Metro station, ticking off the daily AIDS toll in Washington, DC. There in the middle of a gay neighborhood, it was like an electronic bell tolling out the mounting losses in our community, in our circles of friends.

I leveraged my early AIDS articles into a full-time job as a staff writer for the National AIDS Network, a sort of trade association comprised of what quickly became hundreds of AIDS service organizations that were being formed in communities across America. I interviewed, and wrote stories about, women and men who were among the first in their respective cities to step forward and care for their friends and neighbors affected by AIDS.

I met and spoke with people like Ruth Brinker, a retired widow in San Francisco, who began cooking up meals for her gay neighbor in 1984, when she realized he wasn’t able to cook for himself. Her neighborly kindness blossomed into Project Open Hand, the first home-delivered meal service for people with AIDS. Project Open Hand continues to this day, now serving thousands of “medically tailored” meals each day to people who are homebound with life-challenging illness or simply old age.

In a short few months after his diagnosis, Bill himself blossomed into a full-fledged AIDS and gay rights activist. Not only that, but his work as a lobbyist for the American Psychological Association put him in contact with psychologists and other mental health providers across the country who were increasingly becoming involved in developing educational interventions that would help people to avoid HIV.

When Bill died in 1994, he would be recalled as “the father of the HIV prevention lobby in Washington” because of the way he had pressured members of Congress to fund the kind of interventions that the psychologists he represented determined would be most effective. He had spent the eight years between the time of his diagnosis and his death from AIDS working very hard to make sure others wouldn’t follow in his footsteps to a terrible early death. Bill was only 34 years old when he died.

I had been at the hospital nearly every day during Bill’s last weeks. I often fed him when he became unable to feed himself. I brought in my electric razor to shave his face because I knew he’d want to be clean-shaven. We hadn’t been a couple by then for years, but we had remained good friends and, most important from Bill’s point of view, colleagues.

We were fellow warriors in our community’s heroic efforts to rise to the terrible challenges AIDS, and our fellow citizens’ homophobia, imposed on us. I was determined to carry the torch forward after Bill’s death.

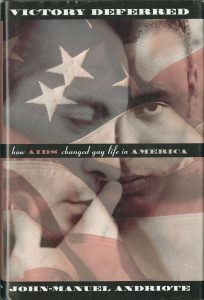

I did that by writing Victory Deferred. My 1999 book was most often compared and contrasted to Randy Shilts’ 1987 book And the Band Played On. I interviewed hundreds of people across the country, read many books and many more articles, and spent more than two years supporting myself with freelance projects while I wrote the book. It was the culmination of many years of cultivating contacts, collecting newspaper and magazine clips, and reassuring myself that I was more qualified than most to write a book about, as its subtitle describes it, “how AIDS changed gay life in America.”

People who interviewed me about the book were surprised to learn that I was already working on another book, completely opposite—in their view—from a “serious” book like Victory Deferred. But as I focused on the 1970s disco era for my 2001 book, Hot Stuff: A Brief History of Disco, it became clear that I had picked just the right subject. Disco music, after all, emphasized celebrating life’s good times even in the midst of hard times. It took off at the time it did because it was just what people needed to help them endure the tribulations of the 1970s: Vietnam, Watergate, gas lines, double-digit inflation.

I knew by then from my experience of so much loss that happy, upbeat music can be just what the doctor ordered to remind us that life is worth living and it has many more joyful moments than sad ones—if, that is, we open our eyes to the joyful ones.

I had already learned important lessons like this by the time my doctor phoned me on October 27, 2005. He was calling to give me the results of my lab tests from my annual checkup the week before.

I wasn’t expecting what he told me. I thought I’d avoided it, dodged the bullet. “I have bad news on the HIV test,” he said.

I trembled, couldn’t believe it. But it was true, as another test later that day in his office verified. Not only was I HIV-positive—after 20 years of reporting on the epidemic as an HIV-negative gay man, as the virus had killed so many of my friends—but further testing found that my immune system was already seriously damaged. I had an AIDS diagnosis!

I was stunned, to put it mildly. I wracked my brain to think how I could have gotten infected, who gave it to me, what we had done and when. That line of thought went nowhere when my doctor told me his records didn’t show an HIV test for the previous three years. I could have been infected several years ago and was only now finding out. I had no symptoms to warn me this was coming.

I was terrified, not only of the virus itself but of the possible side effects of the powerful drugs I had to start taking—and would now have to take the rest of my life. I had diarrhea, couldn’t sleep, and cried a lot. I was also coming apart with worry about how I was going to pay for the medication. I had an individual insurance policy but, nine years before the Affordable Care Act prohibited insurance companies from discriminating against people with “pre-existing conditions,” I now had a pretty major pre-existing condition. I was stuck with a policy that capped prescription coverage at only $1500 a year; my new medications cost more than that a month.

I was able to get into a clinical study at Whitman-Walker Clinic, today known as Whitman-Walker Health, and received free medication and medical care for the first 96 weeks of my new life as a “person living with HIV-AIDS.” That was a major relief. At least it bought me time to figure out what I needed to do for the longer term.

I asked my doctor to refer me to a psychiatrist because I thought I might need an antidepressant to keep me from crying so much. Fortunately the psychiatrist told me I didn’t need medication, that I was crying because it’s natural to cry in the face of suffering—and I was suffering. He said I was actually very resilient, and that this was an “exciting” time in my life because it would give me the chance to re-think almost everything about my life.

One thing I was clear about from the beginning: I did/do not want to be defined by my HIV diagnosis. HIV is something I have; it’s not who I am. I was determined not to let all of my identities be subsumed into a medical diagnosis. I wanted to continue being, simply, John—in all his dimensions.

The psychiatrist’s reference to my resilience got me thinking about my life’s history, the choices and challenges that had brought me to the point of an HIV diagnosis at age 47. Even more importantly, I thought about how I had survived earlier challenges—including my first medical crisis, during my senior year of college in 1980, when my gall bladder ruptured; the death of my father when I was 30 and he was only 52; Bill’s death, and so many other deaths of dear friends.

Somehow I had pulled through each of those terrible experiences, and continued to be the upbeat, optimistic man who has a song for every occasion and can recall song lyrics even from tunes I haven’t heard since I was a boy. Somehow I had always believed I would “get through it”—whatever “it” happened to be—and I would be okay.

It took a move back to my home state of Connecticut in 2007, a return to the place I had fled when I left for college in 1976, to reach a point where I could understand the sources of my resilience. I had to confront the demons of my past growing up in a working-poor family, with a father who became violent when he drank, which was often, in an old New England mill town that had turned in upon itself when the mills fled and jobs for skilled tradesmen became more scarce.

Living away from the safety and reassurance of the gay community and neighborhood where I had lived in DC for more than two decades, I had to rediscover the boy I had been, the places I had explored and hiked decades ago, the interests I had put aside in my urban life, particularly gardening.

I also had to reclaim the man I had become in all my years “away,” as New Englanders put it. I had to work through a lot of shame to reach a point where I could say with more confidence than ever that I am proud of the life I built for myself—and proud to be a gay man, to belong to a community of heroes.

These reflections led to my interest in writing about gay men’s resilience. Drawing from my own experience, from the research I gathered and the interviews I conducted across the country, I wrote my newest book Stonewall Strong, just out in the fall of 2017.

In the book I try to bottle up the “secret sauce” of my and other gay men’s resilience. It has a lot to do with the story we tell ourselves about ourselves, how we frame our story. Are we the hero of our story—or the victim?

In my life, I have had the experience of living among heroes. It’s my life’s mission to share their stories with others—with you—because I know there is healing to be had by learning from them to celebrate our pride as gay men not only on Pride Day, but to live it every day.